A (brief) description of Pliosaurus carpenteri, and comments on pliosaur size estimation

LAST EDITED: 10/3/2025 (Reason: change in way of scaling from percentage difference, to growth coefficient in Abingdon pliosaur section).

“Pliosaurus”, a genus containing enormous carnivorous marine reptiles, is as big of a hunking mess right now. Currently, 6 species are definitively recognised, with other species such as Pliosaurus macromerus and Pliosaurus brachyspondylus being a little more dubious and messy. Most of these species are fragmentary at best or suffer from not the greatest preservation - in recent years, more material has made the anatomy of these giants more clear, however, more often than not only the cranial material is described. Clearly, you can tell that reconstructing these beasts’s a little difficult, which makes size estimation a little harder; many researchers instead opt to use the close relative, more basal pliosaurid Liopleurodon as a basis, which has more detailed descriptions available.

So, how would we go about reconstructing Pliosaurus? I wasn’t going to settle for the simple Liopleurodon head-swap. There are certain specimens referred to Pliosaurus which have extensive postcrania available: Pliosaurus rossicus, one of the largest Pliosaurus species hailing from Russia, has multiple relatively complete specimens housed all over the world - however, I have yet to find a detailed description of any of these lovely specimens, meaning only photos and scans are available. Some Pliosaurus species closer to home are a better fit: CAMSM J.35990, referred to Pliosaurus cf. kevani, is a rather complete postcranial skeleton which has a decent description. This specimen was previously referred to “Stretosaurus macromerus” (a proposed new genus name for Pliosaurus macromerus), however, teeth preserved bear the sub-trihedral appearance characteristic of Pliosaurus kevani, hence why Benson et al. (2013) tentatively referred the specimen to this species (hence why I used this species to reconstruct P. kevani previously). Whilst the postcrania are great for understanding the proportions of this particular individual, the lack of any substantial cranial material (besides teeth and jaw fragments) means that determining the proportion of the skull compared to the body is near impossible. Hence, we need to dig further. Luckily, one species of Pliosaurus preserves a whole heap of postcrania, including most of the skull: Pliosaurus carpenteri.

Recently, I had the wonderful opportunity to look at this material in person at the Bristol Museum. Here, I took photos and measurements of most of the preserved material which has been invaluable in producing a skeletal reconstruction of this animal:

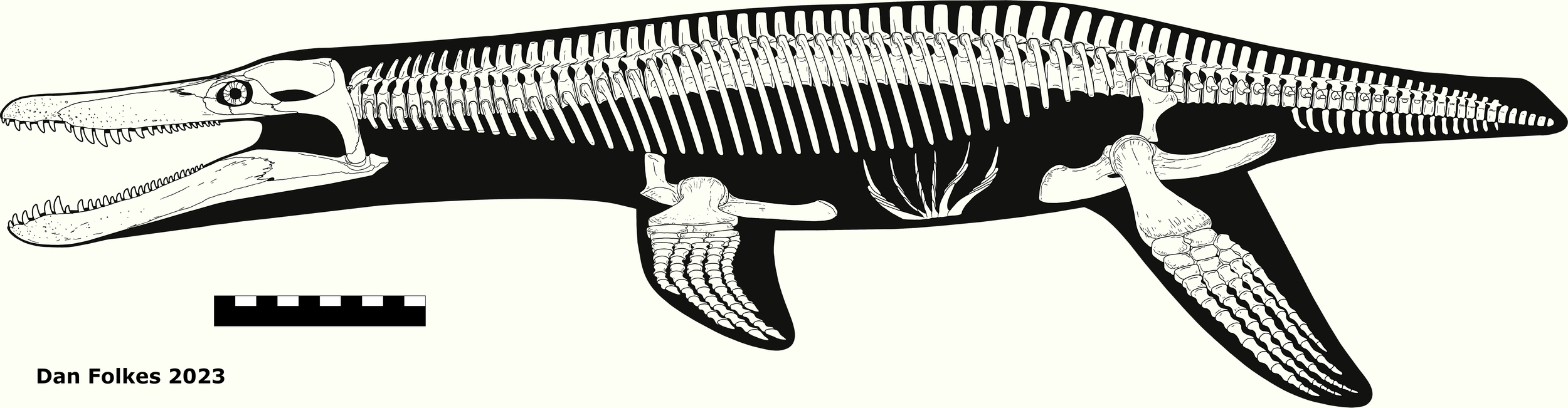

Fig. 1 : Pliosaurus carpenteri skeletal, and rigorous skeletal (white representing known material). Scale bar = 1 metre

Some quick notes on the material of Pliosaurus carpenteri

Skull

The skull is long and broad. The total length of the skull, as preserved, is around 1.8 metres; however, the cranial material has suffered considerable crushing and would have been taller in life. Much of the dorsal surface of the cranium is missing, mostly around the orbit. However, the length of the skull is preserved from the palate as well as the midline of the dorsal surface, enabling a reconstruction to be made. Compared to Pliosaurus kevani, the snout as detailed by the premaxilla is much longer, and the palate wider. The mandible is longer, though still markedly robust despite suffering from crushing. 6 alveoli are preserved in the premaxilla, and at least 7 alveoli are present in the symphysis, though more were probably present in life due to missing parts.

Axial skeleton

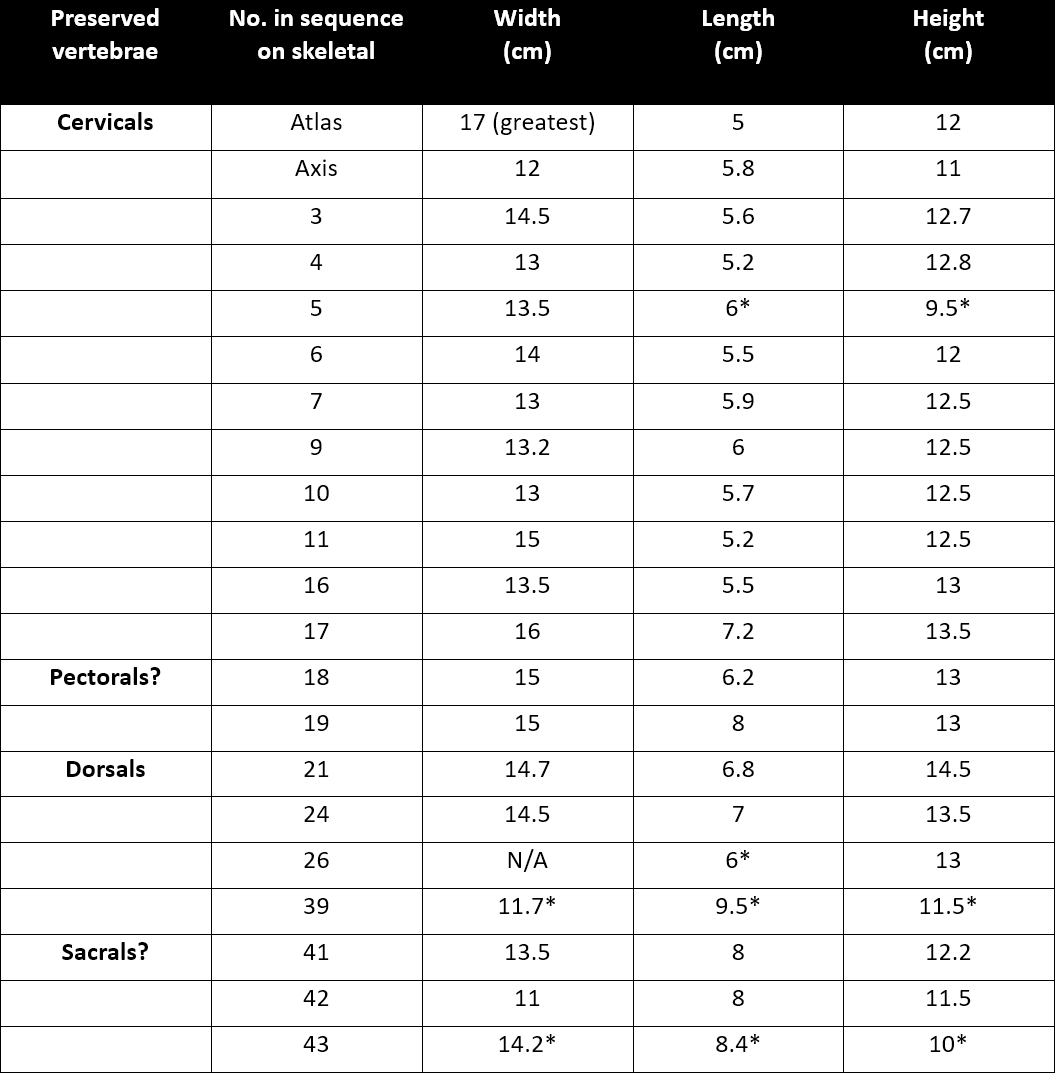

Fig 2. Select few vertebral centra.

A large number of cervicals are preserved; at least 12 including the Atlas and Axis. The centra are short, but wide and tall - although some appeared to have suffered from deformation, most have minimal damage and maintain their original structure. Some are exceptionally preserved. 2 pectorals are possibly preserved, suggested by the presence of rib facets towards the top of the centra. A few dorsal centra are likely preserved, due to the lack of a rib facet along the margin of the centra. The largest dorsal is short but long; though has suffered from considerable weathering, detailing that the original vertebra would have been longer in life. Perhaps 3 sacral vertebrae (or posterior dorsals) are preserved. Unfortunately, these vertebrae are damaged, so the exact position is uncertain. Possible rib facets are preserved towards the dorsal surface, and the length and short height suggest that they aren’t cervicals. Comparison with other Pliosaurus specimens leads to this identification, though as previously stated it is equally possible they are posterior dorsals or anterior caudals. At least 5 neural arches are preserved, including 3 cervical and 2 dorsal neural arches. Only one anterior cervical neural arch is complete, though the other 2 represent a transition along the vertebral series with the posterior-most neural spine being much thicker than the anterior-most. None of the dorsal neural arches preserves the neural spine. Finally, at least 4 caudal chevrons are preserved. Most are long, thick and straight. However, at least one chevron (the longest in the series) is “hook-shaped”.

Appendicular skeleton

Most of the pectoral girdle is preserved, including a left and right coracoid and a left scapula. The left coracoid is much better preserved than the right, which is preserved in various large fragments. It is unclear if the coracoid is broken towards the midline; if not, then the coracoid would have been shaped very similarly to the condition present in elasmosaurs, where there is considerable space in the inter-coracoid region. As this is not the case in any other pliosauroid, I reconstructed this area as incomplete. A more detailed look is needed here. The distal end of the left humerus is preserved, showing that the humerus was fairly large compared to other Pliosaurids (such as Pliosaurus cf. kevani and Sachicasaurus). The radius is preserved, but not the ulna. A good few digits of the forelimb are preserved, with the 1st digit possibly being complete.

Ribs

At least 10 ribs are preserved, including 7 dorsal ribs and 3 cervical ribs, are present. Part of the gastral basket is preserved, represented by most of the medial gastral ossicles. The 6 gastral ossicles are fused, and incredibly thick; the anterior-most and posterior-most ossicles are the largest, with the middle 3 ossicles being much shorter. In dorsal/ventral view, the gastral basket splays outwards, with the 1st and 6th ossicles diverging from the midline at roughly 40-degree angles - this results in a near “spider-like” shape.

A bit about my reconstruction before we get in to the meat of it…

Reconstructing Pliosaurus was definitely a challenge before, but with Pliosaurus carpenteri ’s material, the task is a little easier.

Vertebral count is pretty important when reconstructing, and equally important in reconstructing sizes. Vertebral count ratios differs slightly between genera: Sachicasaurus has a cervical count of 12 cervicals, and 28 dorsals, whereas more basal genera such as Eardasaurus have at least 18 cervicals, 3 pectorals, and 24 dorsals. Liopleurodon, a closer relative of Pliosaurus, has 20 cervicals total (including the atlas/axis). Pliosaurus carpenteri has at least 12 cervicals, and very likely more, suggesting that the body proportions of this pliosaur were more in line with Liopleurodon than brachauchenines such as Sachicasaurus, a fact which was mirrored in my reconstruction - I used a “compromised” ratio, weighted towards Liopleurodon, of 17 cervicals and 24 dorsals (along with 29 caudals), to try and represent a near middle ground. Due to the articulation of the neural spines, it is unlikely there was anymore than 10% intervertebral cartilage between the vertebrae (at least from what we have preserved).

A truly gigantic pliosaur from the Kimmeridge clay formation

The same week I went to see the material of Pliosaurus carpenteri, a remarkably large specimen of (likely) Pliosaurus was described (Martill et al. 2023). Represented by cervical vertebrae (and a possible pectoral), the dimensions of the cervical vertebrae are much larger than those of Pliosaurus carpenteri. It is possible to compare the dimensions of these vertebrae to that of P. carpenteri, and my reconstruction, to estimate the possible size of this particular animal.

Instead of using more broad areas as ratios of the body, here I will compare directly with the vertebrae of Pliosaurus carpenteri (and other Pliosaurus species) to produce size estimates:

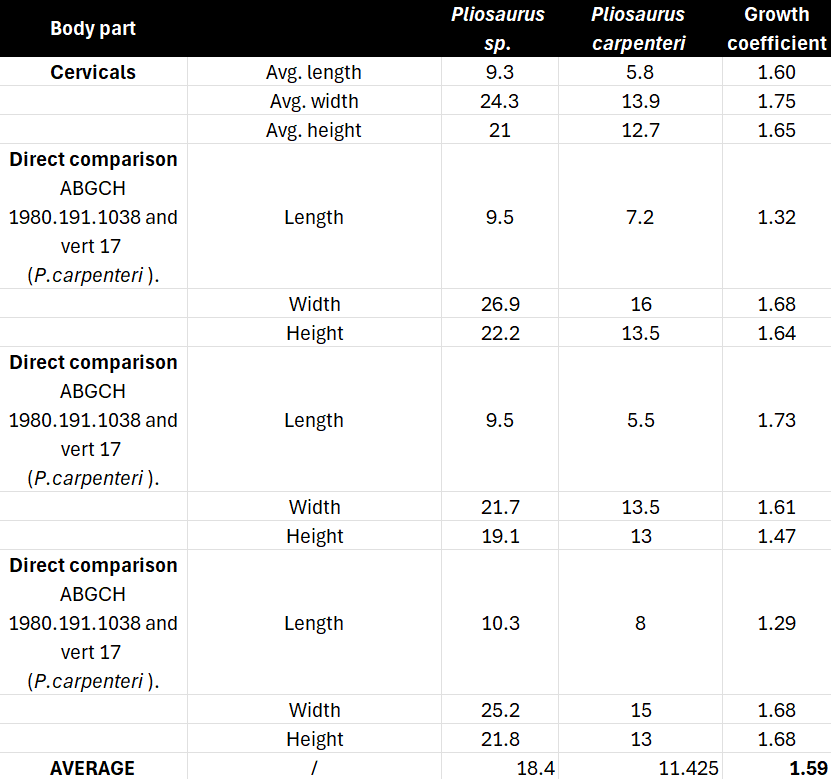

Table 3

Table 3 shows several comparisons between the vertebral measurement of the Abingdon Pliosaur (Pliosaurus sp.) and P. carpenteri, with respective differences in measurement (dimensions of the Abingdon pliosaur divided by the dimensions of P. carpenteri - to create a growth coefficient). An average of all cervical dimensions is followed by a direct comparison between visually similar cervicals (based on size, position, and shape of rib facets, as well as position along the vertebral column).

The growth coefficient in size ranged from x1.75 (highest) to x1.29 (lowest). Using only length, a x1.60 difference between the two specimens is recovered, and a x1.57 difference if an average of the direct comparisons is taken. A total average of all comparisons yields a growth coefficient of x1.59.

As my Pliosaurus carpenteri skeletal is 7.36 metres along the vertebral centra, a size range of 11.6 - 11.8 metres is recovered using the average growth coefficients, with a size range of 9.5 - 12.9 metres using the most extreme percentage differences.

Although not near the 14-metre upper estimate presented in the original paper, this animal is still huge, and a contender for the biggest known pliosaur. It shows some leeway here, and a metre margin of error from my produced estimates is not unlikely. Nevertheless, we can be certain that giant pliosaurs roamed the Kimmeridgian seas.

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks to Deborah at the Bristol Museum for being patient and letting me rummage around the collections looking at Pliosaurus material all day!

Further thanks to Fishboy for comments on some of the Pliosaurus material, which was handy with reconstructions!

References:

Martill, D.M., Jacobs, M.L. and Smith, R.E., 2023. A truly gigantic pliosaur (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation (Upper Jurassic, Kimmeridgian) of England. Proceedings of the Geologists' Association.

Benson, R.B., Evans, M., Smith, A.S., Sassoon, J., Moore-Faye, S., Ketchum, H.F. and Forrest, R., 2013. A giant pliosaurid skull from the Late Jurassic of England. PLoS One, 8(5), p.e65989.

Tarlo, L.B., 1957. The scapula of Pliosaurus macromerus Phillips. Palaeontology, 1(3), pp.193-199.

Knutsen, E.M., Druckenmiller, P.S. and Hurum, J.H., 2012. A new species of Pliosaurus (Sauropterygia: Plesiosauria) from the Middle Volgian of central Spitsbergen, Norway. Norwegian Journal of Geology, 92, pp.235-258.